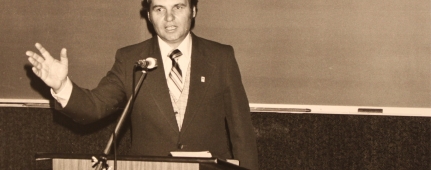

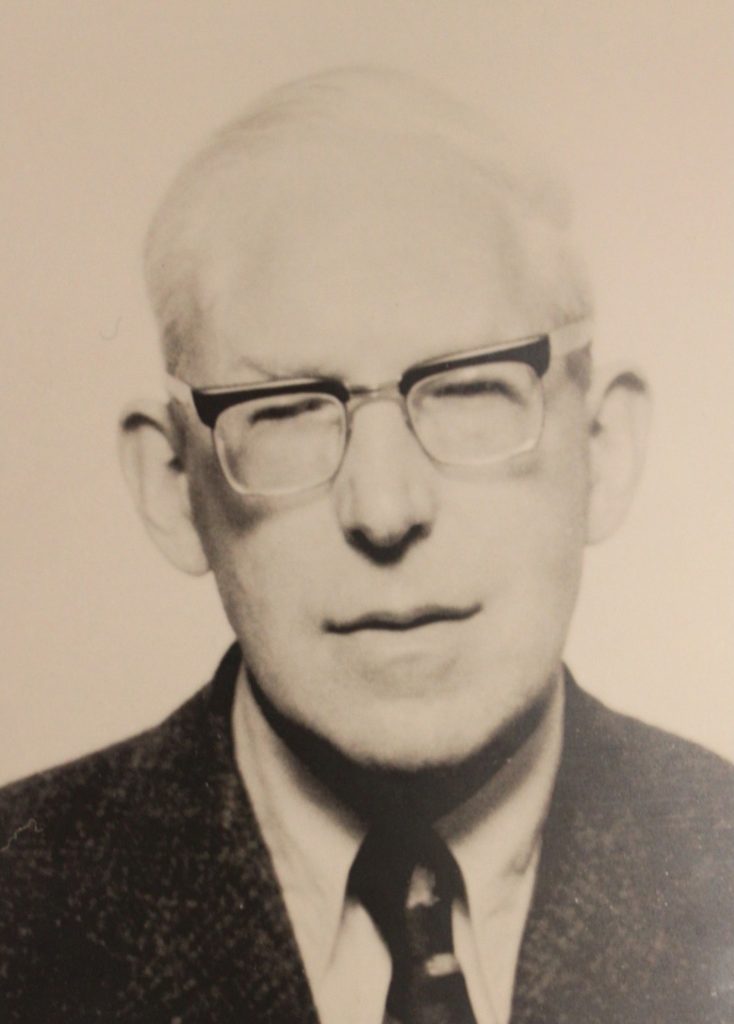

James Innell Packer

(1926-2020)

J.I. Packer was one of the most beloved evangelical Christian leaders of the 20th century. In 2005, Time magazine named him one of the top 25 most influential evangelicals. If there were a Biblical Inerrancy Hall of Fame, Jim Packer would certainly be in it! He certainly belongs in the top ten list (or perhaps even the top four list) of scholars who championed biblical inerrancy in the last half of the 20th century.

Packer was raised in an Anglican home where they didn’t talk much about Christianity. In his teenage years he read the Bible and defended the historic Christian creeds in debates with atheists at school. He read C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity at age seventeen but said later that Christianity was still just an ideology for him and not a personal relationship with God. While studying at Oxford’s Corpus Christi College, he heard a sermon preached by Earl Langston and “the scales fell from my eyes… and I saw the way in.”

Serving as a junior librarian, he became fascinated with books by Puritans like John Owen. The writings of the Puritans were a major influence on the development of his thought life and spiritual life. He was also influenced and nourished by Bishop Ryle and Martyn Lloyd-Jones. In 1948 he felt called to enter into full-time Christian ministry, began teaching Greek and some philosophy at an Anglican seminary near London, and discovered his love for teaching. He remained an Anglican because of its evangelical heritage from the 18th century revivals (e.g., Wesley and Whitfield) and because he wanted to “work from within for true reformation and renewal” (Christopher Catherwood, Five Evangelical Leaders, 1985). Ever fascinated by the Puritan revival of the 17th century, he sought to bring some of its wisdom and warmth to 20th century evangelicalism.

A critical part of his work for reformation and renewal centered around the authority, inspiration, inerrancy, and full trustworthiness of the Scriptures. In Knowing God (IVP, 1973), the book he is most famous for, he plots the course through “five basic truths, five foundational principles of the knowledge of God which Christians have” and sets as the first of the five “God has spoken to man, and the Bible is his Word, given to us to make us wise unto salvation” (Knowing God, 19-20). In his 1995 book Knowing Christianity, he devoted the second chapter to “Revelation and Authority,” which he explained to be the Bible.

The first book Packer published was “Fundamentalism” and the Word of God (Eerdmans, 1958). It sold 20,000 copies in its first year and established Packer’s reputation and high standing in evangelical circles on both sides of the Atlantic. It was a defense of the traditional evangelical view of the Bible against the attacks from liberal Anglicans. Starting as a transcription of talks he gave to students, one of the main reasons it was written was to defend the evangelistic work and the high bibliology of Billy Graham (ref.). Billy’s work was leading countless thousands to make a “decision for Christ” in many countries throughout the 1950s and the liberal-wing of the Anglican church at the time tended to be derisive of Billy’s “fundamentalism” which centered around his view of the Bible as inspired, infallible, inerrant, literally true, and worth believing every part of. Packer defended Graham to the Anglicans. And this book was the initial record and result of it. Although written over sixty years ago about the choice between Liberal Protestantism and Conservative Protestant Evangelicalism, his conclusion of the book echoes as relevant today, even if the names of the camps have changed:

Our argument has shown the real nature of the choice with which this debate confronts us. It is not a choice between obscurantism and scholarship, no between crudeness and sensitivity in biblical exposition. It concerns quite a different issue, and a far deeper one, although critics of Evangelicalism rarely seem to see it, or if they do, are shy of discussing it. The fact is that there we are faced in principle with a choice between two versions of Christianity. It is a choice between historic Evangelicalism and modern Subjectivism; between a Christianity that is consistent with itself and one that is not; in effect, between one that is wholly God-given and one that is partly man-made. We have to choose whether to bow to the authority claimed by the Son of God, or whether on our own authority to discount and contravene a part of His teaching; whether to rest content with Christianity according to Christ, or whether to go hankering after a Christianity according to the spirit of the age; whether to behave as Christ’s disciples, or as His tutors. We have to choose whether we will accept the biblical doctrine of Scripture as it stands, or permit ourselves to re-fashion it according to our fancy. We have to choose whether to embrace the delusion that human creatures are competent to judge and find fault with the words of their Creator, or whether to recognize this idea for the blasphemy that it is and drop it. We have to decide whether we are going to carry through our repentance on the intellectual level, or whether we shall still cherish our sinful craving for a thought-life free from the rule of God. We have to decide whether it is right to make such an idol of nineteenth-century biblical criticism that not even God is allowed to touch it. We have to decide whether to say that we believe the Bible and mean it, or to look for ways whereby we can say it without having to accept all the consequences. We have to choose whether to allow the sovereign Spirit to teach us faith in Scripture as such, or whether to appeal to historians to delimit the area of scriptural assertion within which faith is permissible. We have to choose whether, in presenting Christianity to others, we are going to rely on the demonstration of the Spirit to commend it, or on our own ability to make it masquerade as the fulfilment of secular thought. Evangelicals have made their choice on all these issues. What their critics are really asking them to do is to reverse it: to enter into a marriage of convenience with Subjectivism. But Evangelicals cannot in conscience consent to being thus mis-mated. … Liberalism, as we saw, sets the task of sorting out the divine utterances from the total mass of Scripture by the exercise of our own wits, guided in part by extra-biblical principles of judgment. … discounts the perfection and truth of Scripture in order to make room for man to contribute his own ideas to his knowledge of God. … God’s revealed truth does not need to be edited, cut, corrected, and improved by the cleverness of man.

J.I. Packer, “Fundamentalism” and the Word of God. 170-173.

In 1965, Packer explained this further:

Indeed, analysis shows that the modern ‘broad church,’ liberal, and existentialist positions, however superficially different, are all really members of the same theological family. They are all versions of what we may call Renaissance theology, the Erasmian type of thought within Protestantism. Renaissance theology is characteristically rationalistic, anti-dogmatic, and agnostic in temper . . . Of all these varieties of Renaissance theology, and with them the cross-bred ‘dialectical theology’, which as one foot in the Reformation camp and the other in the Renaissance camp, and shifts its weight from foot to foot according to who expounds it, three things have to be said, Frist these positions are all subjectivist in character–that is, they all depend on denying at some point the correlation between Scripture and faith, biblical revelation and inward illumination, the Spirit in the Scriptures and the Spirit in the heart, and on appealing to the latter to justify forsaking the former. In other words, one only reaches them by backing at some point one’s private view of what the Bible is, or should be, driving against what it actually says, and jettisoning in practice part of what it teaches in order to maintain this private opinion. … Second, these positions are all unstable, for they recognize no objective criterion for truth, nor method for establishing it, save the more or less speculative reasoning of individual theologians, whose conclusions never command full agreement within their own camp, let alone outside it. The pendulum keeps swinging all the time; systems rise and fall; theological fashions, like fashions in the styling of cars or ladies’ hats, rapidly come and go. The first quarter of this century was the age of liberalism, dominated by Troeltsch and Harnack; the second quarter was the age of dialecticism, dominated by Brunner and Barth; the third quarter was the age of existentialism, dominated by Bultmann and Tillich; the fourth quarter has been the age of liberation theologies, chiefly Latin American, black, and feminist; the twenty-first century will no doubt see other fashionable ‘isms’, and other dominant thinkers rising and falling. The truth is that the world of Renaissance theology is a desert of continually shifting sand, where stability is impossible. . . so far as they fail to uphold the authority of the Spirit in the Scriptures over the Spirit in the theologian, and deviate from the task of expounding and applying what the Bible actually says, these positions are really sub-Christian.

J.I. Packer, God has Spoken: Revelation and the Bible. (Baker, 1965, 1979, 1993), 88-90

Also in 1958, John Wenham and Packer founded Latimer House in Oxford to help Anglican Evangelicals to fight against the incursion of theological liberalism. Much of this inheritance–from both Wenham and from Packer–would later funnel into the ICBI. John Wenham’s book Christ and the Bible, for instance, arguably set the tone for all of the ICBI conferences. The first chapter in the ICBI book Inerrancy (Zondervan, 1980, edited by Norman Geisler) was John Wenham’s paper “Christ’s View of the Scriptures.” The seventh chapter is Packer’s, “The Adequacy of Human Language.” The ICBI began with the sharing of these and twelve other papers for discussion prior to forming the articles of affirmation and denial.

Possibly the main thing that all the scholars and leaders of the ICBI held in common, and which the defenders of inerrancy today agree with, is that we believe in the full inerrancy of the Bible because our Lord Jesus treated the Scriptures not just as authoritative but as inerrant. Some of the progressives who take their cue from Karl Barth have over the years tried to undermine the doctrine biblical inerrancy by arguing along the lines of, “We worship Jesus, not the Bible,” “inerrantists are guilty of bibliolatry (making the Bible into an idol),” and “we anti-inerrantists are the truly Christ-centered worshippers.” In contrast, inerrantists like Packer give their allegiance to the Jesus who taught directly and indirectly that the Bible is incapable of containing error (infallible) and has no errors (inerrant). Our allegiance to the Lord Jesus should include allegiance to the view of the Bible (the written word of God) that Jesus (the incarnate word of God) had. And just as it was impossible for Jesus to say anything that was untrue, despite the limitations of the fleshly body that he had taken on, so too it is impossible for the Bible to say anything that is untrue, despite the limitations of the human authors who were writing under inspiration of the Holy Spirit.

In 1966, Packer was one of the many scholars who presented a paper at the Wenham Conference on Scripture at Gordon College in Wenham, Massachusetts. (Not to be confused with John Wenham.) Several participants came from ten different countries. With some exceptions like Packer, H.J. Ockenga, and Kenneth Kantzer, many of the conservative evangelical scholars and leaders who supported biblical inerrancy decided to not go to this conference. The conference, on the whole, affirmed the ultimate trustworthiness of the Bible, along with its authority, but there was a general refusal to consent to the idea that the Bible had zero errors of fact or logic in it. This conference may be seen as the time it became clear that the scholars and leaders of the late-20th century evangelical protestant Christian movement were not united on the answer to whether the Bible contains errors or not. The evangelical movement was clearly split and not inclined to find unity here.

Inerrancy mattered greatly to Packer:

First, why does inerrancy matter? Why should it be thought important to fight for the total truth of the Bible? . . . I, however, am one of those who think this battle very important and this is why. Biblical inerrancy and biblical authority are bound up together. Only truth can have final authority to determine belief and behavior, and Scripture cannot have such authority further than it is true. A factually and theologically untrustworthy Bible could still impress us as a presentation of religious experience and expertise, but clearly we cannot claim that it is all God’s testimony and teaching, given to control our convictions and conduct, if we are not prepared to affirm its total trustworthiness. Here is a major issue for decision. . . So the decision facing Christians today is simply: will we take our lead at this point from Jesus and the apostles or not? Will we let ourselves be guided by a Bible received as inspired and therefore wholly true (for God is not the author of untruths), or will we strike out, against our Lord and his most authoritative representatives, on a line of our own? If we do, we have already resolved in principle to be led not by the Bible as given, but by the Bible as we edit and reduce it, and we are likely to be found before long scaling down its mysteries (e.g., incarnation and atonement) and relativizing its absolutes (e.g., in sexual ethics) in the light of our divergent ideas. . . . once we entertain the needless and unproved, indeed unprovable notion that Scripture cannot be fully trusted, that path is partly closed to us. Therefore it is important to maintain inerrancy, and counter denials of it; for only so can we keep open the path of consistent submission to biblical authority, and consistently concentrate on the true problem, that of gaining understanding, without being entangled in the false question, how much of what Scripture asserts as true should we disbelieve. . .

Packer, Beyond the Battle for the Bible, 17-18.

Is inerrancy really a touchstone, watershed and rallying point for evangelicals . . . what is centrally and basically at stake in this debate, and has been ever since it began two centuries ago, is the functioning of Scripture as our authority, the medium of God’s authority, inasmuch as what is not true cannot claim authority in any respectable sense.

Packer, Beyond the Battle for the Bible, 146.

In 1973, R.C. Sproul called for a conference in defense of biblical inerrancy. Quite understandably, J.I. Packer was among the teachers at the conference. He contributed two chapters to the resulting book, God’s Inerrant Word. Encouraged by the effect of this conference, and seeing the need for something like this but bigger, more international, and more enduring, the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy was planned. But this would be better planned and would invite more of the conservative evangelical scholars in the attempt to correct the errors of the progressive evangelical scholars who had been infected with Neo-Orthodoxy. Packer, Sproul, and Geisler were the main draftsmen of the Chicago Statements produced by the ICBI. J.I. Packer wrote the short expansion of and commentary on the statements. R.C. Sproul wrote the long commentary on the first statement. Norm Geisler wrote the long commentary on the second statement produced by ICBI. Jim Packer was the last living member of the drafting committee for the Chicago Statements produced by the ICBI between 1978 and 1986. With his passing, and with the passing of Norman Geisler (2019), R.C. Sproul (2017), who were also prominent members of the ICBI drafting committee, and other ICBI-friendly, biblical inerrancy stalwarts like Billy Graham (2018), Robert Thomas (2017), and Charles Ryrie (2016), it seems like an important chapter of Church history may be ending. In Packer’s memory, and for the sake of his legacy, we encourage you to download a free PDF version of Explaining Biblical Inerrancy, a book which contains all three of the Chicago Statements and the official commentaries on them. While others champion other important aspects of Packer’s legacy this month, we hope that this part of his legacy will endure too. After the first ICBI summit, Packer hoped “the resulting 3,000-word Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy . . . should be able to function as an agreed platform and referent point for the debates of the next generation.” (Packer, Beyond the Battle for the Bible, 48.)

Did J.I. Packer Approve of Liconean Approaches to Biblical Inerrancy?

As the ICBI era closes, its veterans, one of the threads left loose is question of whether or not Packer, the last of the ICBI breed, endorsed and encouraged the growing trend among evangelicals, typified particularly by Michael Licona in his lectures and books between 2010 and 2017, to use genre criticism on Greco-Roman bioi (GRB for short) to help further define and defend a more sophisticated view of biblical inerrancy. Is the approach that Michael Licona is famous for actually consistent with and in some ways the rightful heir to the legacy of the ICBI? Have Norm Geisler and others on the defendinginerrancy.com team been too hasty in their attempts to warn about and correct some of Dr. Licona’s innovations? Is there a wideness within the fellowship of scholars who identify as evangelicals and inerrantists to embrace Liconean-styled methodology (genre criticism), attitudes, and conclusions all while having some legitimate claim to be working within the parameters set by the ICBI and the Chicago Statements? As part of his tribute to J.I. Packer, and again in his dialogue about the definition of inerrancy with Richard Howe, Michael Licona seems to suggest as much.

Licona and Packer both lectured at the God’s Written Word (GWW) Conference in Canada in 2017. Licona spoke on why there are differences in the Bible and used the idea of “compositional devices” and genre criticism to help explain away some of the statements in the gospels which are not easy to harmonize. According to Licona, at this GWW conference, Packer listened to Licona’s lectures, was quite thrilled with them, and excitedly told Licona, “Agreed! Tops! I agreed with every word!” Also, it is quite true that Packer wrote an endorsement blurb for Licona’s 2017 book on the same topic. And so there seems to be a wedge between Packer and Geisler. Whereas Norm Geisler was keen on arguing against and correcting some of the controversial points Licona has made between 2010 and 2017, Packer it seems, had no interest in correcting anything controversial in the direction Licona is taking maters. He was only encouraging.

Now there is no reason to doubt Packer’s agreement with and enthusiasm over what Licona said at the GWW conference. It is not unreasonable to think that Packer could have agreed with whatever it was that Licona talked about there. (The recordings of the GWW conference are no longer available online but we have saved copies of the MP3 recordings of its sessions.) Licona did not present much that would be likely to be taken as controversial there. And he was clearly trying to solve some difficult differences in the Bible. His two relatively short talks at the GWW do fit well into what Packer himself had written into his short commentary on the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy (CBSI) . Packer, in concert with the other framers of the CSBI, wrote:

We affirm that canonical Scripture should always be interpreted on the basis that it is infallible and inerrant. However, in determining what the God-taught writer is asserting in each passage, we must pay the most careful attention to its claims and character as a human production. In inspiration, God utilized the culture and conventions of his penman’s milieu, a milieu that God controls in His sovereign providence; it is misinterpretation to imagine otherwise. So, history must be treated as history, poetry as poetry, hyperbole and metaphor as hyperbole and metaphor, generalization and approximation as what they are, and so forth. Differences between literary conventions in Bible times and in ours must also be observed: since, for instance, non-chronological narration and imprecise citation were conventional and acceptable and violated no expectations in those days, we must not regard these things as faults when we find them in Bible writers. When total precision of a particular kind was not expected nor aimed at, it is no error not to have achieved it. Scripture is inerrant, not in the sense of being absolutely precise by modern standards, but in the sense of making good its claims and achieving that measure of focused truth at which its authors aimed.

From J.I. Packer’s shorter commentary on the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, in Explaining Biblical Inerrancy, 29.

Based on this, one can see why Packer could have been thrilled with the sound of Licona’s approach, given the short presentations he heard. In that same spirit, biblical inerrantists who respect the wisdom in the spirit and parameters of the Chicago Statements, their official ICBI-sanctioned commentaries, and the ICBI corpus as a whole, should not be quick to dismiss any attempts by Michael Licona, Craig Blomberg, Craig Keener, or any of the other evangelicals who self-identify as inerrantists and use the tools of genre criticism, historical criticism, new historical criticism, or any other form of literary criticism to attempt to shed light upon the Bible. Perhaps we should say that the more scholars we have working on finding good answers to Bible difficulties, the better. And perhaps conservative inerrantists should be wary of throwing babies out with the grey water they see in the bathtub of progressive evangelical scholarship. For better and/or for worse, the ICBI parameters allow the use of the various forms of higher criticism, albeit with caution and without anti-supernaturalistic bias. This may be one of the things that separates fundamentalists from evangelicals. Evangelicals are interested in scholarship and open to the use of methods and tools that fundamentalists are perhaps averse to. We should pay attention to significant contributions to the important field of Bible differences. And Dr. Licona’s contributions are no exception. They are some of the most significant contributions in Q1 of the 21st century. We shouldn’t simply embrace them of course. As always, we should “test everything and hold to what is good. Abstain from every form of evil” (1 Thess. 5:21-22). Even after putting his theories to the test we find some wanting, we should be careful not to discard them all. There may still be some important nuggets to be gleaned.

Perhaps it is good to have a reminder from Packer that the final word on the differences and difficulties in the gospels has not been published and there is still plenty of room for intelligent, scholarly, informed, and even creative approaches. Even so, Packer’s enthusiasm for a part of Licona’s approach does not a blanket endorsement for his entire approach make. Based on his earlier writings, it seems like Packer would be one of the first to point out that higher criticism in its many forms, while technically neutral, has an unfortunate tendency, due to operator error as he or she is carried along by the winds and waves of the age, to be corrosive and erosive to faith in the parts and whole of the Bible.

It is unlikely that the aging Packer, who had lost his eyesight in 2016, was able to read the entirely of Licona’s book Why Are There Differences in the Gospels? What We Can Learn From Ancient Biography, (Oxford, 2017). Did anyone read some or all of Licona’s book to Packer? We can only guess at this point. My guess is that Packer was probably relying more on his memory of what he heard Licona say at the GWW conference than anything else in his endorsement for the book. Perhaps an assistant to Dr. Packer did read some of the book to him. It seems unlikely that most or all of the book was read to Packer. If so, perhaps we shouldn’t consider this endorsement to be all that weighty or all-encompassing. It is likely that Packer was open-minded enough to see that there could be some potential value in this approach and congenial enough to say so. The Chicago Statements do leave an opening for the textual criticism and genre criticism to have some value to biblical studies, so long as the critical studies shed positive light on the text and do not obfuscate, darken, twist, or nullify parts of the text. And perhaps inerrantists should be careful to not throw out any babies with any grey bathwater here. Perhaps there is room to give cautious consideration to some of his theories about “compositional devices” even if we are leery about the underlying assumption that the gospel accounts must necessarily follow patterns found in pagan examples of the Greco-Roman bioi genre. There are other concerns as well, of course. Some of which are documented here, here, and here.

To who may use genre criticism to try to defend or redefine biblical inerrancy, or to redefine what should and should not be considered an “error” based on a sliding scale that includes pagan historiography, the next paragraphs in the short commentary on the CSBI by Packer from 1978 are worth revisiting:

The truthfulness of Scripture is not negated by the appearance in it of irregularities of grammar or spelling, phenomenal descriptions of nature, reports of false statements (e.g., the lies of Satan), or seeming discrepancies between one passage and another. It is not right to set the so-called “phenomena” of Scripture against the teaching of Scripture about itself. Apparent inconsistencies should not be ignored. Solution of them, where this can be convincingly achieved, will encourage our faith, and where for the present no convincing solution is at hand we shall significantly honor God by trusting His assurance that His Word is true, despite these appearances, and by maintaining our confidence that one day they will be seen to have been illusions. Inasmuch as all Scripture is the product of a single divine mind, interpretation must stay within the bounds of the analogy of Scripture and eschew hypotheses that would correct one Biblical passage by another, whether in the name of progressive revelation or of the imperfect enlightenment of the inspired writer’s mind. Although Holy Scripture is nowhere culture-bound in the sense that its teaching lacks universal validity, it is sometimes culturally conditioned by the customs and conventional views of a particular period, so that the application of its principles today calls for a different sort of action.

Explaining Biblical Inerrancy, 30. Emphasis added.

Here we see the technique of stating something positively (affirmations) and then restating it negatively (denials) to form parameters. While the positive statement may invite progressive scholarship with tools and techniques that tend to be associated with liberal and neo-orthodox scholarship, the negative statement nips many weeds in the bud. We hope that the progressive evangelical scholars will take the articles of denial into account and not just the articles of affirmation. In a discussion of the “negative-looking adverbs (‘without confusion, without change, without division, without separation’) in the confession of one Christ with two natures in the Council of Chalcedon, Packer noted that “the words operate as a methodological barrier-fence and guide-rail; a barrier-fence that keeps us from straying out of bounds and digging for gold of understanding where no gold is to be found, and a guide-rail marking out the way to go if we would understand what we believe more perfectly.” In the same way, the ICBI parameters for inerrancy “keeps us within the bounds of the analogy of faith, directing us to eschew interpretive hypotheses that require us to correct one biblical passage by another, on the ground that one is actually wrong, and to explore instead hypotheses which posit a unit and coherence of witness at every point under the Bible’s wide plurality of style. Only those who wish to deny that Scripture is the product of a single divine mind will doubt that this is a real and clarifying help.” (Packer, Beyond the Battle for the Bible, 59-60. Emphasis added.)

Packer was a champion of both the human and divine origins of Scripture. Regarding hermeneutics he wrote:

Believers know that their communicator-God addresses his word–that is, his message–to them in the sixty-six books of Holy Scripture, and that the message concerns new life in and through Jesus Christ. Having heard some part of this message and found fellowship with Christ through it, they now want to receive as much more of it as they can. But the canonical books that comprise the Book in which the message embodied are products of a series of ancient Near Eastern cultures, not identical with each other, and are all (at surface level, anyhow), very different from the scientific, technological, materialistic, comfort-loving, optimistic, sentimental, urbanized, unstable, post-Christian culture of which today’s believers are a part. Also, the Book unfolds its theme of humanity in God’s hands for weal or woe in a way that fallen minds cannot naturally receive in any form. So to ensure that God’s word is heard and not misheard, a threefold discipline must be maintained. Texts must be studied by the historical-critical method, so that we grasp what they meant historically as messages to the humans the writers envisaged as their readers. The principles for doing this constitute hermeneutics in the classical (seventeenth-century) sense. Also, the differences between the modern and biblical-period mindsets must be studied in depth, lest applicatory insight into what these messages mean for us becomes derailed through oversights arising from our modern perspective. The habit of doing this constitutes …

As seen in some of the prior and following quotations, the phrase “all Scripture is the product of a single divine mind” echoed frequently in Packer’s writings.

To the Puritans, Scripture, as a whole and in all its parts was the utterance of God: God’s word set down in writing, his mind opened and his thoughts declared for man’s instruction. … That which was delivered by such a multiplicity of human authors, of such different background and characters, in such a variety of styles and literary forms, should therefore be received and studied as the unified expression of a single divine mind, a complete and coherent, though complex, revelation of the will and purpose of God. … ‘Think in every line you read that God is speaking to you,’ says Thomas Watson—for in truth he is. What Scripture says, God says.

Packer, A Quest for Godliness: The Puritan Vision of the Christian Life, Crossway, 1990, 98-99. Emphasis added.

Interpret Scripture consistently and harmonistically. If Scripture is God’s word, the expression of a single divine mind, all that it says must be true, and there can be no real contradiction between part and part. To harp on apparent contradictions, therefore, … shows real irreverence. ‘…when he sees two Scriptures at variance (in view, though not in truth), Oh, saith he, these are brethren, and they may be reconciled, I will labour all I can to reconcile them; but when a man shall take every advantage of seeming difference in Scripture, to say, Do ye see what contradictions there are in this book, and not labour to reconcile them; what doth this argue, but that the corruption of man’s nature is boiled up to an unknown malice against the word of the Lord; take heed therefore of that.’ It is a striking thought, and an acute diagnosis. Since Scripture is the unified expression of a single divine mind, it follows that ‘the infallible rule of interpretation of Scripture is the Scripture itself, and therefore, when there is a question about the true and full sense of any Scripture…it must be searched and known by other places that speak more clearly.’ Two principles derive from this: (1) What is obscure must be interpreted by the light of what is plain. ‘The rule in this case,’ says Owen, ‘is that we affix no sense unto any obscure or difficult passage of Scripture but what is…consonant unto other expressions and plain testimonies. For men to raise particular senses from such places, not confirmed elsewhere, is a dangerous curiosity.’ (2) Peripheral ambiguities must be interpreted in harmony with fundamental certainties. … These two principles together comprised the rule of interpretation commonly termed ‘the analogy of faith.’

A Quest for Godliness, 102. Emphasis added.

Packer clearly understood that the Bible is a human book. But he emphasized that ultimately the Bible is a product of the mind of God—it is the written Word of God. The human brushstrokes from human minds never overpowers its divine origin. The Bible was primarily the written Word of God, and only secondarily the words of men. Instead of looking for interpretive clues and standards in uninspired, pagan writings, the primary way to interpret the less clear passages of Scripture is in the light of the clearer passages of Scripture.

In 1979, Packer quoted J. Aiken Taylor’s take on the inerrancy debate as being “perfectly said” and worthy of his “Amen:”

The lively issue of Bible inerrancy today is very little a matter of whether one can or cannot find contradictions in the Bible. It is very much a matter of how respectfully one is prepared to treat the material found in the pages of Holy Writ. . . . The essence of the argument is not whether one can or cannot prove or disprove contradictions and errors in Scripture. Millions of words are being wasted on efforts to eliminate alleged contradictions through textual criticism, archaeological findings, interpretive principles. Such efforts are fruitless because one finally is dealing with a foundational attitude towards Scripture and not with the text of Scripture. The issues is one of faith, not scholarship. . . . The debate on inerrancy must go on, for it is foundational to any other debate. . . . At issue is personal spiritual maturity, power in witnessing, and the entire integrity of the Church. Many a minister, discouraged in his own spiritual experience and by the fruitlessness of his ministry, would find the answer in the measure of his commitment to the Word of God—if he looked. The necessary step is one of faith, just as the first step of commitment to Christ is one of faith. One does not pray, “God, help me resolve the seeming contradictions I have found in the Bible.” One rather prays, “God, help me to receive Thy Word wholly, unquestioningly, obediently. Let me make it indeed and altogether the lamp unto my feet and the light unto my pathway.

Packer, Beyond the Battle for the Bible, 61.

Did Packer have a change of heart in his last years? Did he abandon his older adherence to the fight against dehistorization of passages in the gospels and embrace the trend towards liberalizing standards for dehistorization? That seems very doubtful. It is also worth noting that just a few years before the GWW conference, Packer clarified for the DefendingInerrancy.com team that Licona’s use of genre criticism in his book The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach (IVP, 2010) to dehistoricize Matthew’s account of the raising of the saints in Jerusalem was not at all compatible with the parameters of inerrancy set forth in the Chicago Statements. Packer wrote:

“I offer you the following which you may use any way you wish.… As a framer of the ICBI statement on biblical inerrancy who once studied Greco-Roman literature at advanced level, I judge Mike Licona’s view that, because the Gospels are semi-biographical, details of their narratives may be regarded as legendary and factually erroneous, to be both academically and theologically unsound.”

Personal letter to Bill Roach, May 8, 2014

In 2017, in a phone conversation with Norm Geisler, Norm asked him quite specifically if he still supported the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy or if the rumors to the contrary were correct. Norm reported that Jim told him that such rumors were “categorically and absolutely false.” (Additional references: #1, #2, #3.) Given that Packer was not in favor of dehistorization in 2014 and still in line with the CSBI in 2017, it seems quite likely that he would not have been favorable to any attempts to dehistoricize that which is historical or to lower the bar for what qualifies as an error in 2016 had he had been aware of it.

Regardless of Packer’s stances on GRB and dehistorization in his last years of his long and admirable life, regardless of how fully aware he may or may not have been of what he was endorsing, and regardless of how conciliatory he may have been trying to be, we still recommend the parameters set forth by the ICBI in the Chicago Statements, their official commentaries, and the ICBI corpus. We hope that Christian leaders, scholars, pastors, and laypeople around the world will rediscover and reconsider them. We recommend upholding a high standard which insists that there must be a very good reason to dehistoricize a Bible passage that seems to be historical at face value. Settling for poor and highly speculative reasons is going to diminish the logical rigor of our scholarship, diminish our credibility, and lead more people to have additional doubts about the trustworthiness of the Bible.