Billy Graham, Evangelism, Evangelicalism, and Biblical Inerrancy

February 27th, 2018

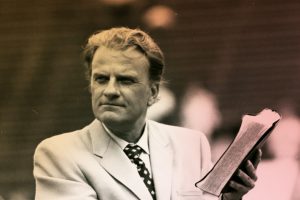

For eighty-two years, Billy Graham’s proclaimed the good news that Jesus died for our sins and arose to offer us eternal life. He preached this gospel to an estimated 210 million people in 185 countries! He somehow managed to earn and keep almost everyone’s respect along the way. No scandals tarnished his reputation and even his harshest critics struggled to find fault with him.

He could have easily retired from evangelism and started a more prestigious seeming career. With his popularity, he could have run for public office, readily become the Senator from North Carolina, and, if his wife Ruth hadn’t forbidden it, could have run for the office of the President of the United States. Many Americans tempted him to run. And—who knows?—perhaps he could have even won by a landslide. But the Lord had called him to be His ambassador, and he wouldn’t stoop to become a politician. Although he did in later life express some regret over being a little too involved in politics on a couple occasions, he managed to do a very admirable job of staying out of politics for the sake of the gospel. In 1980, when Ronald Reagan was running for the office of President and the race was tight, Ronald asked Billy if he could say something on his behalf to the people of North Carolina. Billy replied,

Ron, I can’t do that. You and I have been friends for a long time, and I have great confidence in you. I believe you’re going to win the nomination and be elected President. But I think it would hurt us both, and certainly hurt my ministry, if I publicly endorsed any candidate.

Like the Apostle Paul, Billy tried hard to prioritize the gospel above everything else (1 Cor. 9:12; 2 Tim. 2:10). This policy helped open doors for him to speak in places where others couldn’t. He was still able to preach the gospel openly, if but cautiously, in several Communist countries—Hungary, Poland, Yugoslavia, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Russia, China, and even North Korea—before the fall of the Berlin Wall fell. Astounding! And Billy detested Communism. He considered Marxism/Leninism/Maoism/Stalinism to be some of the greatest enemies of the Christian faith. By choosing his battles carefully, and by putting the kingdom of Christ above the kingdoms of this world, thousands became believers in countries where Christ himself was outlawed. Ironically, Billy’s preaching in those Communist countries helped accelerate the rusting process of the Iron Curtain and the ultimate failure of the push for global Communism.

When Billy passed into glory a few days ago, social media was saturated with traffic tagged #BillyGraham. The vast majority of tweets and posts were expressions of immense respect and sadness over the loss of a treasured person. But some myths, urban legends, and unjustified slander about the man surfaced too. To quickly set the record straight on a couple things, no, Billy did not become a Muslim on his deathbed and, no, he was not a 33rd degree Freemason trying to create a one-world religion. But the misunderstanding that we’d most like to tackle here is the notion that Billy Graham was too focused on the priority of evangelism to care about “lesser matters” like biblical inerrancy.

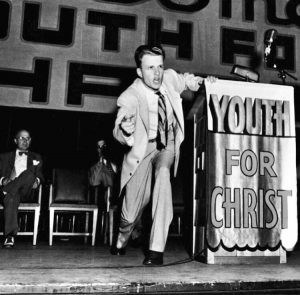

Through a Season of Doubt

In 1948, one of Billy Graham’s friends pulled Billy into a crisis of faith. Charles “Chuck” Templeton and Billy were both evangelists with Youth for Christ. Although it is difficult to imagine now, Chuck was actually the more famous and seemingly more promising of the two evangelists. But Chuck had started to question historicity of the first chapters of Genesis.[1] He shared those doubts with Billy and insisted that it would be “intellectual suicide” to continue to preach the Bible as if were devoid of errors. Chuck also began doubting the Gospel accounts and the deity of Christ. Plagued, he stopped doing evangelism and enrolled in Princeton Divinity School to try to find answers among the professors there.[2] The “answers” he found at Princeton, however, led him to trade his evangelistic zeal for a job in journalism and his evangelical faith for a desupernaturalized, anemic, and sub-orthodox faith. Less than ten years after leaving the ministry, Chuck admitted that he was no longer even convinced that God exists.[3]

Although Billy did not follow Chuck to Princeton like Chuck hoped, Billy’s faith was deeply shaken by Chuck. After his own season of crisis, Billy’s faith had been tested and refined. In Billy’s own words,

The exact wording of my prayer is beyond recall, but it must have echoed my thoughts: “O God! There are many things in this book I do not understand. … I can’t answer some of the philosophical and psychological questions Chuck [Templeton] and others are raising.” I was trying to be on the level with God, but something remained unspoken. At last the Holy Spirit freed me to say it: “Father, I am going to accept this as Thy Word—by faith!” … I sensed the presence and power of God as I had not sensed it in months.[4]

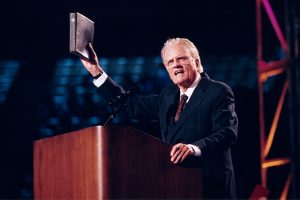

Billy admitted later that this conviction—the conviction that the Bible is the trustworthy, inspired, infallible, and totally inerrant Word of God—was crucial to his evangelism:

The people were not coming to hear great oratory, nor were they interested merely in my ideas. I found they were desperately hungry to hear what God had to say through His Holy Word. I felt as though I had a rapier in my hand, and through the power of the Bible was slashing deeply into men’s consciences, leading them to surrender to God. Does not the Bible say of itself, “For the word of God is quick, and powerful, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing even to the dividing asunder of souls and spirit, and of the joints and marrow, and is a discerner of the thoughts and intents of the heart” (Heb. 4:12)? I found that the Bible became a flame in my hands. That flame melted away unbelief in the hearts of people and moved them to decide for Christ. The Word became a hammer breaking up stony hearts and shaping them into the likeness of God. Did not God say, “I will make my words in thy mouth fire” (Jer. 5:14) and “is not my word like as a fire? . . . and like a hammer that breaketh the rock in pieces?” (Jer. 23:29)?[5]

Historian Christopher Catherwood paints the same picture:

Graham had a spiritual crisis that greatly helped his subsequent evangelism. He had never been to seminary and felt the need for a deeper level of knowledge than he then possessed. A friend of his, Chuck Templeton, had, like himself, become dissatisfied with a certain superficiality in Youth for Christ and had gone to Princeton Theological Seminary to remedy the lack. But the prevailing liberal atmosphere there had caused him to doubt Scripture’s authority. They argued the case together, and slowly doubts began to enter Graham’s mind too. Was his faith as simplistic as Templeton maintained? He … decided to pray to God for guidance. As he did so, he realized that he could not answer many of Templeton’s intellectual queries. But he also knew that from that moment on, he would accept the Bible by faith as the Word of God. The phrase “the Bible says” has become one of his best-known expressions. He has never had any doubt that his unashamed faithfulness to the Word of God, coupled with his totally sincere belief in its truth, has been perhaps the major factor under God in his success as an evangelist.[6]

Billy’s unswerving confidence in the total trustworthiness of the Bible that led to him becoming a major player in the evangelical movement—a movement which would stand with their fundamentalist brothers against the attacks from theological modernists, but would, unlike their fundamentalist brothers, attempt to engage the Academy with a scholarly defense of the faith, focus on evangelizing the world, and not neglect the various social problems. Harold J. Ockenga lists Billy Graham as one of the primary movers and shakers, along with Harold Lindsell, Carl F. H. Henry, Edward Carnell, Gleason Archer, and himself, of the evangelical movement that also began in 1948.[7]

Billy and the Lausanne Covenant

Somewhere in the 1970s, it became very clear that the World Council of Churches Congress (WCC) had lost its saltiness. It had become a voice against the “imperialism” and “colonialism” of missionary work and evangelism in Third-world nations. It had become a mouthpiece for the neo-Marxist gospel of “liberation theology” and armed revolution. Some believed that the KGB agents had infiltrated it. Regardless, evangelicals clearly needed a different kind of congress—one that would stand in opposition to the direction of the WCC and help refocus the evangelical impulse for reaching the entire world with the gospel. In the 1970s, after the Watergate scandal and the Vietnam War, Billy had further distanced himself from American politics and foreign policy. This in turn opened doors to addressing large audiences in the Third-world countries. Everyone involved agreed that Billy Graham should be the honorary chairman of the planning committee for what would in 1974 be called The Lausanne International Congress on World Evangelization. This new congress would not have happened without Billy. And it was huge by anyone’s standards: 2,700 delegates from more than 150 countries arrived in Lausanne, Switzerland, for the congress and 50% were from Third-world countries.

Partially under Billy’s guidance, the Lausanne Covenant, which the Lausanne Congress drafted and signed, included the following propositions about the Bible:

We affirm the divine inspiration, truthfulness and authority of both Old and New Testament Scriptures in their entirety as the only written word of God, without error in all that it affirms, and the only infallible rule of faith and practice. [8]

Billy and the other Lausanne covenant signers believed that it was not even possible for the Bible to contain any errors (infallibility) and that this was somehow either crucial or critical to the mission of reaching the world with the gospel. Today some may have the impression that Billy was willing in 1974 to sign and support the Lausanne Covenant, with its short statement about biblical inerrancy, but was unwilling to sign and support the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy in 1978. This misunderstanding is understandable given the fact that it looks like Billy was front and center on the former and conspicuously absent from the latter. At least two clarifications are warranted.

Both Billy Graham and Francis Schaeffer contributed to the wording of the Lausanne Covenant and signed it. Later both Billy and Francis were surprised and alarmed to see theological progressives in the evangelical ranks abusing its “in all that it affirms” clause. Billy commiserated with Francis about this problem and Francis in turn did try to warn the evangelical world that the wording was too vague to protect itself from abuse by existentialist, Neo-Orthodox Christian thinkers in the evangelical world. Francis warned:

Let us think about what the Lausanne Covenant said about Scripture. I would like to read that to you: “We affirm the divine inspiration, truthfulness and authority of both Old and New Testament Scriptures in their entirety as the only written word of God, without error in all that it affirms, and the only infallible rule of faith and practice.” That was from the Lausanne Covenant. I ought to say—because I know there is some confusion—that that little phrase “in all that it affirms” was not my own contribution to the Lausanne Conference. I didn’t know that was going to be in there until I saw it in its final, printed form. But I would like to speak first about why it is historically a good statement, if left to itself. And that is we are not saying that the Bible is without error in the thing it does not affirm. And the clearest example of course is where the Bible says, “The fool has said that ‘There is no God.’” The Bible does not teach that there is no God. The Bible does not affirm that. But I would want to make a point beyond that: we are not saying that the Bible is without error in all the projections which people have made on the basis of the Bible. What we’re saying is what the Bible really affirms is without error. So that statement, as it appears in the Lausanne Covenant, is a perfectly good statement. But as soon as I saw it in its printed form, I knew that it was going to be abused. And it has been abused. I have a letter from Billy Graham, dated in August. And this is what he wrote to me: “Dear Francis, I was thinking about writing a brief booklet on ‘all that it affirms,’ which I took to mean the entire Bible. Unfortunately, this statement is being made a loophole by many. And unhappily…”—though he is absolutely right and I thank God that he sees it to be so—“…this statement, which is good in itself, when taken in a historic context of meaning, yet nevertheless has indeed been made a loophole by many.” How has it been used as a loophole by many? Well, it is following still the existential methodology. And that is that the Bible affirms—I’m using now the words of the Lausanne Covenant—the Bible affirms the value system and the meaning system set forth in the Bible and certain religious things such as the physical resurrection. But, on this basis of the existential methodology, to these men they would say in the back of their mind, even as the covenant is signed, “but the Bible does not affirm anything without error in the area of history in the cosmos.” And with tears we can say that without any question people signed the Lausanne [Covenant] just where Billy put his finger and that is using this thing, which is good in its self, in a historic basis, but nevertheless they used it as a loophole to read it this way. Because of the widely accepted methodology [where] religious things being separated and isolated from what the Bible teaches in the areas open to verification (that is history) and those things science would deal with (the cosmos). Because of the widely accepted existential methodology therefore in themselves—and listen to me please—this is not an easy speech for me to make—because of the widely accepted existential methodology in certain parts of the evangelical system, therefore in themselves the old words of [hits the pulpit] infallibility, inerrancy, without error, are meaningless today, unless some such awkward phrase is added as the Bible is without error not only when it speaks of values, and meaning, and religious things, but when it speaks of history and the cosmos as well. If some such phrase is not added, these dear words to us can become meaningless.[9]

Although the Lausanne Covenant is an excellent statement about many things, and has a fine statement about biblical inerrancy (in so far as it is not abused), both Francis and Billy came to see it as an inadequate statement on biblical inerrancy. Consequently, both men would soon begin to play very important roles in promoting the work of the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy (ICBI) in the late 1970s. The Lausanne Covenant fell short when trying to explain inerrancy and the ICBI’s statements on biblical inerrancy and hermeneutics became the answer to that. The Lausanne Covenant, unlike the Chicago Statements, did nothing to answer some of the other challenges that the Chicago Statements addressed—challenges like the use of the intentionalist view of truth instead of the correspondence view of truth and the use of genre criticism (or other forms of higher criticism and any other hermeneutical gymnastics) to deny the historicity of a biblical narrative or excuse an apparent contradiction.[10] Even today some progressive evangelicals today prefer to point to the Lausanne Covenant as their preferred standard of inerrancy.[11]

Why didn’t Billy Sign the Chicago Statements on Inerrancy?

It is true that Billy did not publicly endorse the ICBI between 1977 and 1988. It is also true that Billy did not sign any of the three Chicago Statements produced by the ICBI. But there is more to the story. For the sake of the gospel, Billy had to be very careful with his public endorsements. Similar to the way Billy was unwilling to publicly endorse Ronald Reagan for President, despite the fact that he privately wanted to do so, and similar to the way Billy did not publicly warn against the loophole in the Lausanne Covenant but instead privately worked with Francis Schaeffer to sound the warning, so too Billy decided (with considerable reservation) that he would not publicly endorse the ICBI in its infancy. But he did support it privately in ways that most people do not know about.

The papers from the ICBI are archived in twelve boxes in a climate-controlled room in one of the libraries at Dallas Theological Seminary. In the second box, there are a few letters from Jay Grimstead, who played a tremendous role in getting the ICBI going, and Billy Graham. In these letters, Jay attempted to enlist Billy’s support for the ICBI. Since these are private letters, we will not reproduce them here. But the following conclusions may be drawn from them about Billy’s stance in 1977:

- Billy decided that he should not take a public stand on biblical infallibility and inerrancy

- He believed that inerrancy was not an issue that should cause some to break fellowship with others over

- He believed firmly and deeply in biblical infallibility and full inerrancy

- He was very concerned about the progressive revolution away from the historic, evangelical position on the Bible. He seems to have been not just aware of but in agreement with Harold Lindsell’s assessment of the battle for the Bible within evangelicalism. He was very concerned about the attacks on the Bible by Neo-Orthodox scholars and was in favor of a scholarly response.

- He believed the very word “inerrancy” was weak by itself and in danger of being redefined in various ways

- He was keenly interested in the council’s work and followed its progress

- It was difficult for him to turn them down and his heart was with them

- He didn’t voice any disagreement with the many reasons Jay gave for the council

- He made recommendations for the council (which were heeded)

- He committed to supporting inerrancy in his own ministry

- He quietly and anonymously gave a generous donation to the ICBI to support its ministry in its infancy

Signing the Bible Petition

In 2013, both Billy Graham and Franklin Graham, and about 40,000 others, signed “the Bible Petition” at https://defendinginerrancy.com///sign-the-petition/ which says:

I affirm that the Bible alone, and in its entirety, is the infallible written Word of God in the original text and is, therefore, inerrant in all that it affirms or denies on whatever topic it addresses.

Billy’s acceptance of this statement was done publicly. He was making a public stand in the wake of several breaks with the affirmations and denials of the Chicago Statements on Inerrancy and Hermeneutics made some scholars in the Evangelical Theological Society. His signing of the Bible petition was in response to the drift away from the evangelicalism that he helped create. His signing of the petition was also on a website that very clearly promotes the Chicago Statements as the evangelical norm.

Conclusion

As we pray for the Lord to raise up more men and women to be his ambassadors and empower them like He empowered Billy, we should not imagine that the Lord will bless the work of someone who doesn’t have a comparable trust in the Bible as fully trustworthy. And as for the future of the evangelical movement, we should think twice about moving away from the evangelicalism that Billy and his friends set the tone for.

Recommended Resources

Billy Graham: A Life Remembered | Billy Graham TV Special

A Tribute to Billy Graham

Reflections on the Passing of Rev. Billy Graham, One of the Greatest Christian Heroes of Our Time

Billy Graham’s 99th Birthday: Notable Reflections

The Cross – Billy Graham’s Message To America

Endnotes

[1] “But, Billy, it’s simply not possible any longer to believe, for instance, the biblical account of creation. The world wasn’t created over a period of days a few thousand years ago; it has evolved over millions of years. It’s not a matter of speculation; it’s demonstrable fact.” This quote of Templeton is from Stacia McKeever and Ken Ham’s article “The Slippery Slide to Unbelief: A Famous Evangelist Goes from Hope to Hopelessness” in Creation 22, no 3 (June 2000): 8-13. Also https://answersingenesis.org/jesus-christ/resurrection/the-slippery-slide-to-unbelief/. Templeton was actually quite wrong: the neo-darwinian theories about macro-evolution have all failed to be demonstrated in long running experiments with bacteria and fruit-flies. And if it won’t happen with “simple organisms,” it certainly won’t happen with the more complex ones.

[2] Templeton wrote, “I had gone to Princeton hoping to resolve some of the questions that were eroding my faith. Paramount among them was the question: Who was Jesus of Nazareth? Was he a moral and spiritual genius or was he, as the Christian church has always held, ”very God of very God”? … During the day, I spent my spare time in the library or in conversation, questing, searching. The foundation of Christianity is the person of Jesus. If he was a man, however gifted, he could be no more than a superlative teacher and a soaring example. If I was going to continue in the ministry, I would need to know that Jesus Christ was enough. By the end of my third year at Princeton I had found a measure of certainty, not through enlightenment but through a conscious act of commitment. It was enough.” From http://www.templetons.com/charles/memoir/evang-princeton.html

[3] Quoted in D. A. Carson and John D. Woodbridge, “If I Had to Do It Again.” In God and Culture: Essays in Honor of Carl F. H. Henry, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1993) 392-393.

[4] Billy Graham, Just As I Am: The Autobiography of Billy Graham (San Francisco: Harper-San Francisco, 1997), 139. Cited in Woodbridge, p.136.

[5] Billy Graham, “Biblical Authority in Evangelism,” Christianity Today 1, no. 1 (1956) cited in Woodbridge.

[6] Christopher Catherwood, Five Evangelical Leaders (Harold Shaw Publishers: Wheaton, IL. 1985) 198.

[7] Harold J. Ockenga wrote this in the forward he wrote for Harold Lindsell’s Battle for the Bible (Zondervan, 1976) 19.

[8] The Lausanne Covenant may be read at https://www.lausanne.org/content/covenant/lausanne-covenant

[9] Francis Schaeffer, “The Watershed of the Evangelical World.” Starting at 19:56. https://youtu.be/cXvzvivdVlA?t=19m56s. Norman Geisler recalls that in one of the early, formative meetings of the ICBI, Francis supported the use of the word “inerrancy” but preferred the phrase “without error.”

[10] Dr. Norman Geisler discusses these in his forward to Explaining Biblical Inerrancy (Bastion Books, 2013). https://defendinginerrancy.com///free-book-in-honor-of-r-c-sproul-explaining-biblical-inerrancy/.

[11] In a dialogue with Dr. Bart Ehrman, an agnostic whose path parallels Chuck Templeton’s well, Dr. Michael Licona wrote, “The Lausanne Covenant, signed by more than 3,000 evangelicals, including Billy Graham and the late John Stott, states that the Bible is ‘without error in all that it affirms.’ … I continue to be a biblical inerrantist and I’m content to define inerrancy as found in the Lausanne Covenant. … In my opinion, the definition found in the Lausanne Covenant is sufficiently vague as to allow a high view of Scripture while avoiding the need to overdefine ‘inerrancy.’ I think the Chicago Statement has a fairly good, though imperfect, definition of what biblical inerrancy is and is not.” https://thebestschools.org/special/ehrman-licona-dialogue-reliability-new-testament/michael-licona-interview/. Similarly, Dr. Licona responded to another person who expressed concerns about Licona’s views, “It’s a pity that you think that, Grant, since I don’t embrace the position you attribute to me. I may not hold a view of biblical inerrancy that’s as rigid as the one you hold. But that’s a far cry from thinking the Bible ‘fumbles in many facts.’ I embrace the Lausanne Covenant.” https://academic.logos.com/dr-mike-licona-how-to-overcome-doubt-and-strengthen-your-faith/

Download the official commentary on the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy by R.C. Sproul from here.

Subscribe to the Defending Inerrancy Newsletter by clicking here!