Were the New Testament Manuscripts Copied Accurately?*

Joseph M. Holden, PhD & Don Stewart, MA (New Testament)

Because scholars don’t possess the original writings of the New Testament (known as autographs), we must ask: How accurate are the manuscript copies (apographs)? For if the copies do not reflect the original writings of Scripture, we would have no idea what the original texts said. Because there were no copy machines available in ancient times, the tedious transmission process had to be accomplished by the scribe’s own hand. Hence, copies were called “manual-scripts” or manuscripts.

As modern scholars conduct a careful analysis of the manuscript copies, it is obvious that the New Testament text contains minor scribal “mistakes.” This has led some to erroneously assume the Bible is not inspired or inerrant in all that it states, claims, teaches, and implies. This false assumption emerges from the notion that all New Testament copies produced through the centuries must be exact replicas of the original text. That is to say, with regard to the time when the New Testament was originally written until the time the printing press was invented, some have demanded that the scribes copy the text 100% accurately, or it can’t be considered inspired or inerrant. They conclude that because the scribes fell short of perfect transmission, an inspired and inerrant Bible is impossible. However, there are several reasons Christians believe the New Testament manuscripts were copied accurately (despite minor scribal mistakes) and why it can still be considered the inspired and inerrant Word of God.

To understand this issue better, we should familiarize ourselves with the process Bible scholars undertake in their effort to reconstruct the original text. Scholars diligently work like forensic scientists analyzing a crime scene, carefully examining the evidence left behind so they can reconstruct what originally happened. Similarly, by evaluating and comparing the textual evidence (known as textual criticism), scholars can then work backward to establish what was originally written. Our English Bible is the culmination of this textual investigation.

Examining the Textual Evidence

There are three main areas of textual evidence to consider when answering the question of whether the New Testament manuscripts were copied accurately: (1) the number of Greek manuscripts, (2) the dating of the manuscripts, and (3) the textual accuracy of the manuscript copies.

The Number of Greek Manuscripts

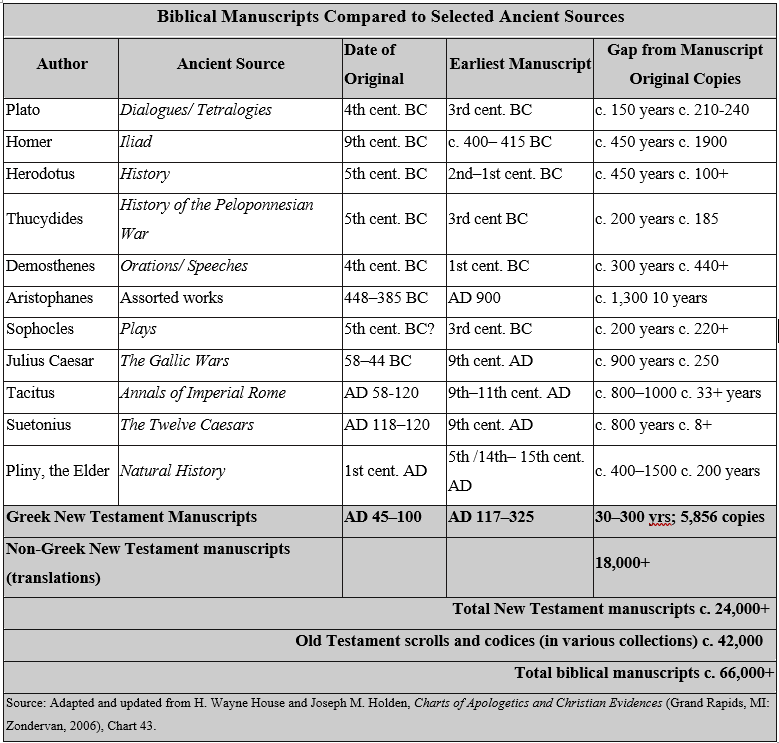

The New Testament possesses the highest number of manuscripts of any book from the ancient world (prior to AD 350). To better understand the scope of the numbers involved, as of 2017, the Institute for New Testament Textual Research, located at the University of Munster in Germany, currently lists the official number at 5,856 partial and complete manuscript copies written in the Greek language.1 These include handwritten copies of the New Testament papyri, parchment and lectionaries. If we add to this number more than 18,000 New Testament manuscripts written in other languages (translations) besides Greek, the overall count swells to more than 24,000 New Testament manuscripts! Because the versions are in a different language from the original Greek, they are not as valuable as the Greek manuscripts in reconstructing the text. However, they are still important witnesses to the text’s reliability and transmission.

We can appreciate the robust number of New Testament manuscripts by comparing it with the number of manuscripts available for other works from the ancient world. For example, the second-most-supported work behind the New Testament is Homer’s well- known poem Iliad, with about 1,900 manuscripts.2 Ancient literature was rarely translated into another language—with the New Testament being an important exception. From the very beginning, Christian missionaries, in their attempts to spread the gospel, translated the New Testament into the various languages of the people they encountered. These translations, some made as early as the middle of the second century, give us an important witness to the text of that time. The greater number of manuscripts available gives scholars added confidence when it comes to reconstructing the original New Testament text, for it offers a textual “check and balance” when comparing and contrasting the various manuscripts. For example, if one manuscript is missing a passage of Scripture, a scholar needs only to consult the numerous other copies. Alternatively, if any ancient work were to come down to us in only one copy, there would be nothing with which to compare that copy. In such a case, there would be no way of knowing whether the scribe was incompetent, for the text could not be checked against another copy.

Additional witnesses to the accuracy of the New Testament text, which are among the Greek manuscripts, are the lectionaries. The church followed the custom of the Jewish synagogue, which had a fixed portion of the law and the prophets read each Sabbath. In the same manner, Christians developed the practice of reading a fixed portion of the gospels and the New Testament letters every Sunday (and on holy days). These fixed portions are known as lectionaries. Surviving fragments of lectionaries come from as early as the sixth century AD, while complete manuscripts are dated from as early as the eighth century. Interestingly, the more than 2,400 copies of lectionaries that still exist reveal greater care in their transmission than other biblical manuscripts. Because we possess so many manuscripts (from various sources and geographical areas), scholars can have confidence the original biblical text has been well preserved. Consequently, translators never have to rely on blind guesses when determining what the text originally said. The text has come down to us in an accurate manner, with nothing lost in its transmission.

The Early Manuscript Dates

The time span between the date the work was originally completed and the earliest existing copy available to us is significant. The length of this time-span is a crucial element of discovering the accuracy of transmission and confidence we place in reconstructing the original text. Usually, the shorter the time span, the more dependable the copy. The longer the interval between the original and the copy, the more room there is for errors, embellishments, and distortions to creep in as the text is copied and recopied.

Fortunately, this time span for the New Testament manuscripts is relatively short, with the earliest manuscript copies currently ranging from 30-300 years from the original texts. In our modern culture, 30-300 years seems like a long time, but for historians of ancient literature, it is like yesterday! The earliest published New Testament manuscript fragment we possess today, the John Rylands Fragment (also called P52), contains a small portion of John 18. Most scholars date the fragment anywhere from AD 117– 138, which, at its earliest, is only about 30 years removed from the original writing of the Gospel of John. In addition, paleographers have documented at least 120 Greek manuscripts that date to within three centuries of the original composition of the New Testament.3 Among these are at least 76 manuscripts, many being fragments, that date prior to the reign of Emperor Constantine (AD 306-337). What is more, in 1972 the late professor Jose O’Callahan of the University of Barcelona, in his article New Testament Papyri in Cave 7 at Qumran?, claims to have identified a small Greek papyri fragment (7Q5) among the Dead Sea Scrolls that could date prior to AD 70. He identifies the Greek letters found on the fragment as belonging to a portion of Mark 6:52-53. In 1982, German scholar Carsten Thiede supported O’Callahan’s earlier findings in The Earliest Gospel Manuscript? where he argued forcefully for the same conclusion. Though it is important to recognize that O’Callahan and Thiede’s conclusions about 7Q5 are debated even among conservative scholars, the implications of their discovery open the door for establishing pre-AD 70 manuscript evidence supporting the early dating and accurate transmission of the synoptic gospels.

The entire New Testament text is accounted for in manuscript form within 300 years of the original writing (cf. Chester Beatty Collection, Bodmer Collection, Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus). Christians can truly appreciate the excellent position the New Testament occupies regarding the early dates. For the best writings of the ancient Greeks—such as Plato, Aristotle, Herodotus, Thucydides, and Homer—the time span between the original writings and the earliest copies is often more than 1,000 years. In most cases, only 5 to 20 manuscripts support these ancient non-Christian works. In the case of Homer’s Iliad, the time span is about 400 years, and, as mentioned earlier, is supported by nearly 2,000 manuscripts. A comparison with other literary works from the ancient world reveals a growing number of New Testament documents and their early dates, as well as the increasing number of manuscripts from the ancient world.

John Warwick Montgomery comments on the strong bibliographical standing the New Testament enjoys when he says, “To be skeptical of the resultant text of the New Testament books is to allow all of classical antiquity to slip into obscurity, for no documents of the ancient period are as well-attested bibliographically as the New Testament.”4

Another early witness to the accuracy of the New Testament text comes from the prolific writings (of hundreds of thousands of quotations of Scripture) of the ante-Nicene fathers of the church. For example, seven letters have survived that were written by Ignatius (AD 70–110), and nearly every book of the Bible (except 2 John and Jude) was quoted by AD 110 by only three individuals—Ignatius, Clement of Rome, and Polycarp. In those seven letters, Ignatius quoted from 18 different books of the New Testament. Every time he cited Scripture we can observe the Greek text he was using. Consequently, the early fathers provide us with an excellent early witness to the text. For this reason, their prolific writings remain an important testimony to the New Testament.

The number of quotations from the church fathers is so overwhelming that if every other source for the New Testament (Greek manuscripts and versions) were destroyed, the vast majority of the New Testament text could be reconstructed! Although the exact percentage of how much of the New Testament could be reconstructed from patristic quotations has not been exhaustively calculated and verified yet, estimates above a 95% reconstruction rate in no way seem unreasonable or overly optimistic. Because of this, any impartial person cannot help but be impressed with their abundant testimony. To dismiss these areas of support would be self-defeating, for it would mean that every extrabiblical ancient work considered “reliable” by secular scholars—all of which are based on lesser literary evidence—would need to be brought into question.

Accurate Transmission and Variant Readings

When a manuscript(s) differs in wording from the base text, the result is known as a “variant reading.” Because of the innumerable times the New Testament has been copied over the last 2,000 years, these variants have crept into the text. Some scholars estimate that 400,000 or more of these variants (errors) exist in the New Testament text. However, using the word error to describe these deviations from the original text can give the wrong idea and is often misleading. Technically speaking, any deviation from the base accepted text is an error, but the kinds of “errors” represented in the New Testament text are not errors of historical, geographical, spiritual, or scientific fact. Instead, they are rather trivial. Therefore, the term “variant(s)” has been employed by scholars to avoid this confusion, since misspellings, omissions, differing word orders, updated words (substitution), and additions are much different in nature than errors of fact that would threaten biblical inerrancy or the truth value of the message.

There is no doubt that the scribes who copied the texts introduced changes. These scribal changes can be broken down into two basic types: unintentional and intentional. The greatest numbers of variant readings found in the New Testament manuscripts are unintentional variants. They could creep into the text through fatigue or through faulty sight, hearing, writing, memory, or judgment on the part of the scribe. Despite these variants, Daniel Wallace of the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts writes, “It is quite true that (virtually) no viable variants are major threats to inerrancy…”5

Other variations came about intentionally, as New Testament Greek scholar J. Harold Greenlee notes.

These comprise a significant, although a much less numerous, group of errors than the unintentional changes. They derive for the most part from attempts by scribes to improve the text in various ways. Few indeed are the evidences that heretical or destructive variants have been deliberately introduced into the mss [manuscripts].6

Thus, the intentional variations, for the most part, were the work of scribes attempting to make the text more readable, not change the meaning. This is the important difference between updating the text (editing) and altering its meaning (redaction). The late Princetonian scholar and renowned authority on New Testament textual criticism Bruce Metzger expands upon the intentional variations. He writes,

Other divergences in wording arose from deliberate attempts to smooth out grammatical or stylistic harshness, or to eliminate real or imagined obscurities of meaning in the text. Sometimes a copyist would add what seemed to him to be a more appropriate word or form, perhaps derived from a parallel passage.7

The charge that is often made, without qualification—especially by New Testament scholar Bart Ehrman—is that copyists radically changed the substance of the text. Again, the facts speak otherwise, as Michael Holmes explains: “Occasionally the text was altered for doctrinal reasons. Orthodox and heretics alike leveled this charge against their opponents, though the surviving evidence suggests the charge was more frequent than the reality.”8

The amount of intentional variation to the text was minimal. The text was carefully copied, and discerning Christians, who were dispersed throughout the entire Roman Empire, would have made it difficult for malicious changes to be introduced. There is simply no evidence of widespread altering of the text for doctrinal reasons. Furthermore, the variant readings, whether intentional or unintentional, exist in only a very limited portion of the New Testament.

Two of the greatest textual scholars who ever lived, Brooke Foss Westcott and Fenton John Anthony Hort, had this to say concerning the amount of variation in the New Testament manuscripts: “If comparative trivialities, such as changes of order, the insertion or omission of an article with proper names, and the like, are set aside, the words in our opinion still subject to doubt can hardly amount to more than a thousandth part of the whole New Testament.”9

B.B. Warfield made a similar assertion when he wrote, “[The New Testament] has been transmitted to us with no, or next to no, variation; and even in the most corrupt form in which it has ever appeared, to use the oft-quoted words of Richard Bentley, ‘The real text of the sacred writers is competently exact.’”10 Textual criticism experts Maurice A. Robinson and William G. Pierpont note the following situation in which we find the text of the New Testament:

For over four-fifths of the New Testament, the Greek text is considered 100% certain, regardless of which textype might be favored by any critic. This undisputed bulk of the text reflects a common pre-existing archetype (the autograph), which has universal critical acceptance. Note…that most of the variant readings found in manuscripts of other textypes are trivial or untranslatable. Only about 400-600 variant readings seriously affect the translational sense of any passage in the entire New Testament.11

Therefore, when all the variants of the New Testament are considered, we are dealing with only 400 to 600 variants that have any effect on the translation of the text. What is more, church historian Phillip Schaff estimated that of the 400 variants that have affected the sense of the passages in the New Testament, only 50 of these are important.12 Facts like this led textual scholars Kurt and Barbara Aland to make the following observation concerning the text of the New Testament:

On the whole, it must be admitted that…New Testament specialists… not to mention laypersons, tend to be fascinated by differences and to forget how many of them are due to chance or normal scribal tendencies, and how rarely significant variants occur— yielding to the common danger of failing to see the forest for the trees.13

Whatever manuscript tradition we use as the basis for a given translation, the outcome will be substantially the same because the text is basically the same. Whether one prefers to use the Byzantine text type, which is found in the greatest number of manuscripts, or the Alexandrian text type, which has fewer but older manuscripts, the final result will be more or less the same. They all tell the same story! That is to say, the words (verba) may vary slightly, but the voice or meaning (vox) is the same. For example, consider the following illustration offered by Norman Geisler that describes the relationship between variant words and meaning:

1. YOU HAVE WON TEN MILLION DOLLARS

2. THOU HAST WON TEN MILLION DOLLARS

[Notice the King James bias here]

3. Y’ALL HAVE WON $10,000,000

[Notice the Southern bias here]

Observe that of the 28 letters in line 2, only 5 of them [in bold] are the same in line 3. That is, about 19 percent of the letters are the same. Yet, despite the bias, the message is 100 percent identical! The lines are different in form but not in content. Likewise, even with the many differences in the New Testament variants, 100 percent of the message comes through.14

This is a powerful illustration of why we can acknowledge that our manuscript copies contain variants and yet, at the same time, we can state with confidence that the Bible is inerrant. In other words, the words may change slightly, but the meaning is still the same. The voice of God is heard loud and clear in the text! This is seen in the Gospel of Matthew, where the author cited and made allusions to the Old Testament more than 100 times. Even in places where loose paraphrases were used, we can still recognize those allusions as Scripture.

Despite these variants, scholars have recognized the great accuracy with which the New Testament manuscripts were copied. Metzger claimed that the Hindu Mahabharata was copied at about 90 percent accuracy and Homer’s Iliad at about 95 percent accuracy.15 As noted in the illustration above, if 90-95 percent accuracy is achieved in the transmission process, it would be more than enough to communicate 100 percent of the original meaning of the text. Other notable Bible scholars, such as Ezra Abbot, figured the copies of the New Testament manuscripts are 99.75 percent accurate.16

Westcott and Hort calculated the New Testament’s accuracy at 98.33 percent by asserting that only one-sixteenth of variants rise above the level of trivialities.17 Greek scholar A.T. Robertson places the transmission rate at 99.9 percent accurate, believing only a thousandth part of the New Testament text was of any real concern.18 Even New Testament critic Ehrman, writes, in his Misquoting Jesus, “Most of the changes found in our early Christian manuscripts have nothing to do with theology or ideology.”19

Confidence in the Research Results

Based on the various kinds of evidence, it is clear that great care was taken to accurately copy the Greek manuscripts. Thus, we can be confident that the text of the New Testament, as it stands today, is substantially the same text that was originally written by the writers of Scripture. Undoubtedly, the quantity of New Testament manuscripts, the dates from the original manuscripts to the earliest copies available, and quality of the copies of the New Testament manuscripts all serve as undeniable and powerful witnesses to the accurate preservation of God’s inspired and inerrant Word.

Endnotes

*Adapted for defendinginerrancy.com from Joseph M. Holden, gen. ed., The Harvest Handbook of Apologetics (Eugene, OR: Harvest House Publishers, 2019), 191-198. Copyright © 2019 by Joseph M. Holden and Don Stewart. All rights reserved.

1. See the tally by The Institute for New Testament Textual Research at http://www.uni-muenster.de/INTF/KgLS GII2010_02_04.pdf. To keep updated on the ever-growing tally, see the searchable database at http://ntvmr.uni-muenster.de/liste.

2. See Martin L. West, Studies in the Text and Transmission of the Iliad (Munchen, Germany:K.G.SaurVerlag, 2001), 86ff, and the more recent work by Graeme D. Bird, Multitextuality in the Homeric Iliad: The Witness of the Ptolemiac Papyri (Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies, 2010).

3. See Joseph M. Holden and Norman Geisler, The Popular Handbook of Archaeology and the Bible: Discoveries that Confirm the Reliability of Scripture (Eugene, OR: Harvest House, 2013), 111-130.

4. John Warwick Montgomery, History and Christianity (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1971), 29.

5. Daniel B. Wallace, The Number of Textual Variants: An Evangelical Miscalculation at https://danielbwallace.com/2013/09/09/the-number-of-textual-variants-an-evangelical-miscalculation/, accessed on July 27, 2017.

6. J. Harold Greenlee, Introduction to New Testament Textual Criticism (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1964), 66.

7. Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, d ed. (Stuttgart, Germany: German Bible Society, 1994), 3-4.

8. David Alan Black and David S. Dockery, eds., New Testament Criticism and Interpretation (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1991), 103.

9. B.F. Westcott and F.J.A. Hort, The New Testament in Greek (New York: MacMillan, 1957), 565.

10. Benjamin B. Warfield, Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament (London, UK: Hodder & Stoughton, 1907), 14.

11. Maurice A. Robinson and William G. Pierpont, The New Testament in the Original Greek According to the Byzantine/Majority Text Form (Atlanta, GA: Original Word Publications, 1991), xvi-xvii.

12. Phillip Schaff, A Companion to the Greek Testament and the English Version (New York: Macmillan, 1877), 177.

13. Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1987), 28.

14. Joseph M. Holden and Norman Geisler, The Popular Handbook of Archaeology and the Bible: Discoveries that Confirm the Reliability of Scripture (Eugene, OR: Harvest House, 2013), 128.

15. Bruce Metzger, Chapters in the History of New Testament Textual Criticism (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1963), 146.

16. B.B. Warfield, An Introduction to Textual Criticism of the New Testament

(London, UK: Hodder & Stoughton, 1886), 13-14.

17. Brooke Foss Westcott, Fenton John Anthony Hort, and W.J. Hickie, The New Testament in the Original Greek (New York: Macmillan, 1951), 2.2.

18. A.T. Robertson, An Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament (London, UK: Hodder & Stoughton, 1925), 22.

19. Bart Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why (NewYork: HarperSanFrancisco, 2005), 55.